A Data-Driven Look into Haiti’s Healthcare System

By Sylvie T. Rousseau, Castelline Tilus, Morgan Mendis, Yvel Marcelin

April 2, 2021

During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we want to take a moment to examine disparities within the Haitian health system. Though at the time of writing it appears new cases of the disease have significantly declined in the country, with 12,663 total confirmed cases and 250 deaths as of January 27, 2021 according to government reports (US State Department), it has highlighted disparities with differential impact in different communities. From January to June of 2020, COVID-19 produced a case fatality rate (# deaths/# cases) of 1.6% in the Ouest region where the capital is located, versus a case fatality rate of 7.8% in the Grande-Anse region (CoronaHaiti.org). Observing such wide differences drives us to question existing structural factors in the healthcare system that may help us understand these inequalities, and ultimately recommend policy to address them.

Many factors influence the performance and inequality in healthcare systems. The events of 2020-2021 have shown us that though a country may have very sophisticated components, it must support them with strong system-wide approaches or risk leaving its population vulnerable. In the context of low- and middle-income countries, available information about illness and health behaviors may be insufficient to allow service providers and policy decision-makers to make real time adjustments in the midst of rapidly evolving events.

To help drive informed policy in both public and private sectors, Ayiti Analytics was created as a startup dedicated to helping raise the veil on complex issues by bringing data to the forefront. We seek to lift some of the mystery for our international readers concerning health disparities in Haiti, and provide a starting point for a more informed discussion of health systems within the country.

This article has two parts. First, we present an overview of the types of facilities and associated personnel within the Haitian healthcare system, then we look specifically at the geographic distribution of facilities, equipment, and medical personnel and dissect the equity of distribution among the population. Our primary data source is the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) of 2017-2018, a health facilities survey conducted by the Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) and the Demographic and Health Surveys Program (DHS) with the support of the Haitian government, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), The Global Fund, and the World Bank Group. By reviewing the distribution of medical and healthcare resources, we provide additional evidence in the conversation on health equity throughout the country’s diverse Départements and communes. In our analysis, we identified clusters of health facility resources and analyzed the resulting vulnerability created across the country by the unequal access to medical resources.

We encourage you to explore the full series of charts and data tables available in this dashboard.

Part 1

While Haiti is among the least developed countries in the Western hemisphere, there has been a strong change in key health indicators over the past 25 years according to the Demographic and Health Surveys conducted by USAID. Utilization of health services has seen an 8% increase between 2016 and 2017, infant mortality has decreased from 74 to 59 per 1,000 live births, prenatal health provision has increased by 23%, and adoption of modern family planning methods has increased more than twofold (+19%). Despite considerable progress, important challenges remain: only about 40% of women give birth in a health center, the prevalence of HIV in the general population remains stubborn at around 2%, and there is still a large unmet need for health services like family planning, oral health checks, and mental health provision. [DHS, pg 10]

Table 1. Total Clinical Facilities by Facility Type

2017-2018 Service Provision Assessment (SPA)

Graphs

For More Information on Part 1 Click Here

Many Actors, Common Goals

The Ministère de Santé Publique et de la Population (MSPP) is Haiti’s governmental health agency, regulating health training and licensing for over 7,800 health professionals, and protocols and policies for over 900 public and private hospitals, clinics, and local health centers throughout the country. [DHS, p. 21] The MSPP works at the national, departmental, and local level to administer provision of key equipment and services in partnership with the hospitals and health providers. This national ministry also mediates cooperation with international bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and USAID, and numerous local and international non-profit groups. These groups serve the Haitian population in various ways, with MSPP as a central hub for coordination.

MSPP has developed its internal methods of self-evaluation that largely fall in line with the World Health Organization’s Framework for Health System Performance Assessment, and it regulates international actors accordingly. MSPP takes an operational approach, outlining key services and structures required, as well as clear targets for health metrics to be achieved. It has begun the immense task of centralizing health system data in a digital resource, the Système Information Sanitaire Nationale Unique SISNU, with well-defined data points that are comparable throughout the country and provide actionable information across different settings. This database is accessible to health officials, and contains health service provision data, including utilization data, services provided by illness type, and outcomes of different conditions. It is fed by monthly reports from a network of facilities.

In 2012 MSPP published a ten-year high-level plan for health, with the central goal to expand the reach of health services to all households, including in the most hard-to-reach places. This document, the Plan Directeur de Santé 2012-2022 (PDF, French) lays out the general structure of the health system into primary, secondary, and tertiary care, with primary care divided into three echelons. Each level has recommended personnel, materials, and services, and the overall design is intended to function in an integrated way to ensure an efficient continuum of care. MSPP’s complementary Paquet Essentiel de Services (PDF, French) was launched in 2016 and in 342 pages further details the most essential services the national health system must offer.

Structure of the Haitian Health System

MSPP has categorized the nation’s health structures into clinical (public, private for-profit, private non-profit, and mixed funding), para-clinical (labs, dialysis centers, pharmacies and pharmaceutical labs, ambulance facilities, etc.), and training centers. Among the first group of clinical facilities, MSPP further recognizes clinics and hospitals of differing size, coverage area, and service type. While citizens may not know the formal classifications, it is clear that a vaccination may be received at a local dispensary, while surgery must be performed at a hospital.

Facilities and Community Reach

Haiti’s 1,033 health facilities are embedded in residential, commercial, rural, and urban milieus and range broadly in size and capacity. Their entrances are prominently marked, with walls identifiable to passerby with white and bright green paint, but care is not limited to the physical installation. Rather, the concept of community health is central in the primary care strategy to reach every household. The government-trained Community Health Worker, termed Agent de Santé Communautaire Polyvalent or ASCP, spends the majority of his or her time in the field serving as the most visible public interface with the health system. They will visit individual families to follow up with cases that have not returned to the clinic, lead health education workshops, and support nurses and doctors in administering certain vaccinations and medicines in the locality via rally posts and other community outreach activities. Additionally they are usually responsible for recording service and health status data for around 1,000 people or households, though this number varies.

ASCPs are primarily associated with community health centers, Centres Communautaires de Santé (CCS), per MSPP recommendations, though they may be associated with other types of health facilities, especially in urban settings. Table 1 summarizes the number of health facilities in Haiti by categories defined by MSPP. These range from CCS to large hospitals, and run the gamut of provision of care, with variation in staffing and available supplies. CCS, the most numerous type of facility, are first-line neighborhood health centers that respond to basic health questions. They are usually only a few rooms in size and may be staffed only by auxiliary nurses, who operate somewhere between the skill level of certified nursing assistants and medical assistants who can take vitals and initial medical histories.

The second most common type of health facility is the Centre de Santé (CS), larger facilities with multiple personnel and patient beds for observation or overnight stay. In these facilities, you can receive skilled care from both general physicians and nurses of different categories. In a CS, expect availability of in-house laboratory sample collection and basic analysis with light microscopy and common reagents, as well as basic pharmacy services. A CS faces many demands, providing services for a wide gamut of health issues including: women’s and maternal health, child health, infectious disease, nutrition, non-communicable and chronic disease, ocular health, mental health, surgery including vaginal infant delivery, bucco-dental health, and emergencies including acute sickle-cell management.

Three categories of hospitals provide an additional echelon of care in Haiti: the Community Reference Hospital (Hôpital Communautaire de Référence, HCR), the Departmental Hospital (Hôpital Departemental, HD), and the University Hospital (Hôpital Universitaire, HU). The former two are identified primarily by their geographic situation and service catchment area. Whereas the HCR is located in the city which serves as the seat of the Arrondissement, similar to the idea of a county or parish in other countries, the HD is located in the Departmental Capital, roughly the equivalent of a state or province. The HCR will have a catchment area of 150,000 to 250,000 people. All types of hospitals offer an array of primary, emergency, and specialist care, including radiology, laboratory, and pharmacy services on-premises. They serve their localities, and receive referrals for more complicated cases from smaller health centers in the area.

The HU is a hospital associated and administered by an institute of higher learning, which serves as a teaching hospital for a large number of training medical students. There are only a handful of HU in Haiti, including the State University Hospital, Hôpital Universitaire de l’État d’Haïti (HUEH) and Hôpital Universitaire de La Paix (HULP) in the Port-au-Prince metro area, the Hôpital Universitaire Justinien (HUJ) in Cap-Haïtien, and the Hôpital Universitaire de Mirebalais (HUM) in the central plateau, among others. This is a state-of-the-art hospital built by the nonprofit Partners in Health, and is known in the international health community for being the largest solar-powered hospital in the world. The HUs offer specialty care for the general populations and unique groups, for example the Nos Petits Frères et Soeurs group which cares for children. They also train the next generation of providers, and often pioneer newer technologies and therapies.

To further illustrate the different types of health facilities, let us consider health needs surrounding pregnancy and birth: an ASCP may be the first point of contact for a pregnant woman, visiting her often, bringing prenatal vitamins, and helping her form a birth plan. The ASCP may direct her to a CCS, to help a woman who’s missed a menstrual cycle confirm pregnancy and provide prenatal care, or connect her with a traditional birth attendant who can visit during the course of the pregnancy and assist her in coming to the CS. Uncomplicated deliveries may be performed in a special room within the CS or a local hospital which has a larger delivery ward, with more beds and equipment. There they will most likely have access to sonography machines and anesthesia equipment to be able to handle complications during delivery, as well as expertise to handle perinatal complications. Hospitals will have the personnel and capacity to perform caesarean sections. Following birth, hospitals are more able to link the patient to care from social workers, psychologists, and breastfeeding and child nutrition counselors. All levels of care are meant to be interdependent and work together to provide health services to the most remote locations, while escalating care as needed.

Additional Structures

Facilities that provide essential services in support of the health system include national laboratories, the pharmaceutical supply chain, the national ambulance network, and the educational and training institutions for health workers.

There is one national public lab and a host of private labs, concentrated in the Port-au-Prince metro area and larger cities such as Gonaïves, Cap-Haïtien, and Les Cayes. The Laboratoire Nationale de Santé Publique (LNSP) is the primary public laboratory which houses advanced equipment for automated analysis of lab samples. It serves the whole country in running PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests to determine the viral load of HIV particles, for example. The only other laboratory facility with capacity to run PCR analysis is at IMIS (l’Institut des Maladies Infectieuses et de Santé de la reproduction), a lab operated by the large nonprofit GHESKIO.

Also integral to health culture in Haiti are the informal sector and traditional medicine. Though pharmacies are available in almost every community, more common still are sellers of drugs of questionable origin and efficacy in marketplaces and along roads. Traditional healers offer important spiritual and community support, and increasingly western medicine has sought to partner with these influential leaders to advance the cause of health. Additionally, a host of herbal remedies also hold significance in the lives of Haitians of all socio-economic levels.

Healthcare Workforce

According to USAID’s Health Finance and Governance project, Haiti faces a severe shortage of health workers including doctors, nurses, and midwives. “With only 0.65 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 people, Haiti falls well below the World Health Organization’s recommendation of 4.45 doctors, nurses and midwives per 1,000 people. The nation has approximately 15,660 health workers of all cadres: 8,469 personnel in the public health sector—of whom approximately 88 percent are concentrated in urban areas—and 7,191 in the private health sector.” Beyond doctors and nurses, numbers of other essential service providers also lag behind demand, with a great need for psychologists and social workers, radiology technicians, and professional hospital administrators. This lack of dedicated human resources for health is one of the main challenges in meeting the overarching goals of the health system, and unlike acute drug and equipment shortages, it is a challenge that can only be addressed with long-term dedicated policy change and commitments of resources.

There are only five medical schools in the territory of Haiti that train doctors with MD degrees to practice within national boundaries. Relationships with the neighboring Dominican Republic and Cuba (Kirk & Kirk, 2010, 166) have reinforced medical services in times of crisis, and allowed Haitian additional doctors to be trained abroad and return to practice in Haiti. MSPP recognizes 87 training institutions for nursing science throughout the country, Recommendations have been made concerning modernization of the professional Haitian pharmacist and training of pharmacists and technicians, but the national system still lags behind the desires of the cadre. Two pharmacist training programs currently exist in Haiti, with many pharmacy technician programs of varying competency. The government body that authorizes and certifies all these programs is the Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale et de la Formation Professionnelle.

Part 2

Geospatial distribution of health facilities and associated vulnerability

Health Systems Vulnerability Score in Haiti

We used a quantitative approach to measuring health systems capacity in Haiti by assigning a vulnerability score to each commune based on publicly available data found in the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) survey. Key indicators include the number of full-time medical staff, the availability of laboratory diagnostic services, infection prevention measures, the number of overnight and in-patient beds, among other factors that indicate readiness to provide care. We aggregated these scores, and then assessed which geographic regions are the most vulnerable. Our vulnerability score identifies the regions in Haiti that are best and least-equipped to provide care or respond to public health threats like COVID-19. This is not meant to be a definitive ranking of communes, facilities or departments; it is rather a starting point for a broader conversation on health systems inequity in Haiti, and will be updated with any newer official data.

Methods

Methods – Two Vulnerability Scores

We explored two approaches to create a score to evaluate communes based on their relative health system vulnerability.

Uniform Vulnerability Score: Uniform Ranking of Variables

The first scoring model was based on calculating a uniform weight of all the input variables within one of the five thematic areas of: Health System Capacity, Diagnostic Capacity, Infection Prevention, Personal Protective Equipment, and Therapeutic Readiness. Each thematic area was given an equal weight of 20%. Then the weight of each individual variable was a fraction of the overall weight of thematic area. This method was very simple to apply in the programming and allowed the research team to quickly check assumptions and determine the relative vulnerability of different communes.

Select Vulnerability Score: Subjective Weighting of Variables

The second approach that we explored was a subjective score that was informed by discussion between the research team and healthcare providers in Haiti. The subjective score also assigns weights to each thematic area based on the relative importance of that area to contribute to the overall assessment of health system vulnerability. Please note that the conversations that directed this subjective model mostly occurred in April to August 2020, during the global COVID-19 pandemic. The breakdown of weight assignment to each feature in the model is described below:

Health System Capacity 40%

• Number of health facilities 14.29%

• Number of generalists, full-time 14.29%

• Number of lab assistants, full-time 14.29%

• Number of lab technicians, full-time 14.29%

• Number of nurses, full-time 14.29%

• Number of pharmacist, full-time 14.29%

• Total full-time staff 14.29%

Diagnostic Capacity 20%

• Stethoscope 33.33%

• Thermometer 33.33%

• X ray machine 33.33%

Infection Prevention 20%

• Improved water source 33.33%

• Regular electricity 33.33%

• Soap and running water or else alcohol-based hand disinfectant 33.33%

Personal Protective Equipment 10%

• Latex Gloves 50.00%

• Medical Masks 50.00%

Therapeutic Readiness 10%

• Inpatient care 25.00%

• Number of hospital beds 25.00%

• Oxygen-filled oxygen cylinders 25.00%

• Referral capacity-functional ambulance at facility 25.00%

Comparison of Methods

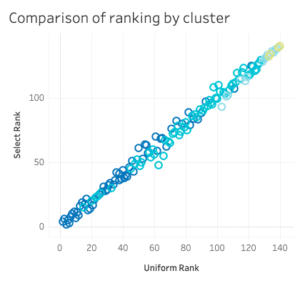

We compared our two scores to assess how much overlap there was between both approaches using Pearson Coefficient Analysis to determine the strength of the linear relationship between two variables. The two scores have a Coefficient of 0.9978 (P-Value <=0.00001)).

This would suggest that using either approach would have yielded a very similar result. Since the Uniform Ranking method was easier to calculate that would be the preferred option for the future.

The final step we apply to evaluate our Vulnerability Score Model is to apply an unsupervised machine learning technique in order to determine if we can isolate any hidden features to help us classify the communes vulnerability assessment. We generated a K-Mean clustering algorithm which we fit to our dataset to calculate a clustering label for each commune. Using the clustering labels we reviewed our vulnerability scores and found that there was high success and that the clusters align with the relative rankings created by both the Uniform and Subjective scores.

Refer to this document for additional information regarding the clustering model

Data Sources & Data Limitations

Evaluating the vulnerability scores that we created is difficult without data regarding healthcare outcomes at the commune level since we are attempting to suggest which communes are more likely to have poor health outcomes. Data on important health outcomes is recommended for further research.

We use data from the 2017-2018 Service Provision Assessment [link to PDF] (SPA) survey in Haiti, a nationally representative survey of health facilities implemented by the Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) through the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program. The 2017-2018 SPA survey is the most comprehensive assessment of health facilities in Haiti, reporting data from 1,033 health facilities within the country. The SPA fills an urgent need for documenting service gaps and monitoring health system strengthening efforts in Haiti and other developing countries.

But as with any data collection method, there are advantages and disadvantages of utilizing survey data. Nationally representative surveys like the SPA are effective tools for collecting information, but they create a snapshot of the population at a specific point in time (The Demographic Health Survey and SPA are conducted every 5 years). As such, the data are comprehensive, but they do not capture real-time data on health facility capacity. It should be noted that not all communes and facilities are recorded in the SPA. We thus have null data in the Nippes Department, where the Commune of Plaisance du Sud had no data reported. This is visualized as gray points in the charts.

Discussion of Results

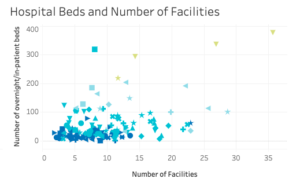

Our analysis shows that there is a severe lack of capacity at the national level (there are 7 hospital beds per 10,000 people in Haiti compared to 16 hospital beds per 10,000 people in the neighboring Dominican Republic, and in 2017, annual spending on healthcare per person was $48 USD in Haiti compared to $10,243 USD in the United States). At the commune level, we find that there is great disparity in the number of communes that fall within the least vulnerable and most vulnerable clusters.

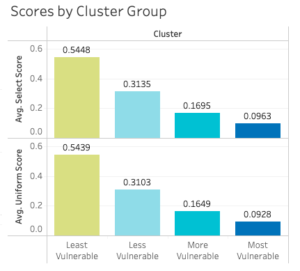

Here we have the distribution of the two vulnerability scores, showing the number of communes that fall within each of the four cluster groups, Least Vulnerable, Less Vulnerable, More Vulnerable, and Most Vulnerable. The difference between the Most and the Least Vulnerable is stark: 0.4485 points in the Select Score and 0.4511 points in the Uniform Score on a scale of 0 to 1.

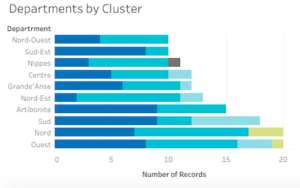

In the figure below, we show the same four clusters distributed across the ten geographic-administrative Departments of Haiti. We notice that the Nord (North) and Ouest (West) Departments are the only places which contain “Least Vulnerable” communes, shown in green. Also, Artibonite has the largest share of Most Vulnerable communes in dark blue. Factors that may contribute to this include an expansive, arid, and mountainous terrain and frequent protest activities which cut off main transport arteries from the capital, vital to resupply and patient transportation. More research is needed to draw further conclusions.

Note that while the Ouest, Sud (South), and Sud-Est (South-East) have the same apparent number of Most Vulnerable communes, these communes vary in geographic and population numbers, so we cannot draw direct comparisons. We would like to layer population density on this in a future analysis to dig deeper.

Plaine du Nord, Milot, Quartier Morin, and Tabarre (communes in the Nord and Ouest Department) are ranked as the Least Vulnerable communes, boasting more full-time medical staff and hospital beds than neighboring regions. Among the most vulnerable communes include La Valle, Grand Goave, Tiburon among others.

Population Centers Do Not Track with Resource Availability

In the analysis of the Least Vulnerable communes, we noticed that the commune of Milot ranks high, which tracks with our understanding that the Hôpital Sacré Cœur de Milot is a long-established hospital and center of excellence with broad support from domestic and international sources. It made sense that such an elite hospital was located in a commune which ranked among the least vulnerable. However, not all excellent or well-resourced hospitals exhibited this pattern, and further investigation into related factors may be called for. An example is the Hôpital Universitaire de Mirebalais, a teaching hospital which enjoys patronage from Zanmi Lasanté (the local Partners in Health NGO, founded by Paul Farmer profiled in the book Mountains Beyond Mountains), continuous capital improvement projects, and attracts patients from Port-au-Prince.

Questions for Further Investigation

Our analysis indicated several possible directions for future research. Among these include (1) Which variables most accurately predict vulnerability score? (2) What changes can be observed based on more updated data? (3) How many patients does a facility receive from within its commune vs from neighboring communities? Does the portion of a center’s patients who originate from the same commune vary with facility type as expected? (4) Is the proximity to another commune with a good health facility an important factor in the Most Vulnerable communities’ health outcomes? Indeed, in Haiti, it is very common for someone to live in commune X but go to hospital in commune Y because Y has a bigger hospital. For example, Limonade (Most Vulnerable) is 10-15 min away from Quartier Morin (Least Vulnerable) and maybe 40 min to Milot (Least Vulnerable). (5) What differences can be appreciated between areas with high concentrations of private clinics compared to those with more public clinics?

Annex

Methods – Health Indicators by Department

Methods – Data Processing

In processing the data several transformations were applied to facilitate the comparison of communes of drastically different population sizes. The data in its raw format was reported at the facility level, we aggregated all the facility features to their respective administrative commune. This way the number of Staff represents the total number of staff reported across all facilities in a commune. Please see Figure 1 to view variation across unadjusted features.

The next transformation was to calculate the health system capacity at the per 100,000 people rate. We normalized the statistics by the size of the population in the respective commune. Below in Figure 2, we see the additional variation across several features from population-adjusting the metrics.

The final transformation on the dataset is a log transformation to adjust the distributions of the dataset to fit a Gaussian distribution. We can see in Figure 3 the final output and the clear variation across all the datasets once we have applied the log transformation to every value. When the values were zero, we added a small value of 0.01 so as not to cause an error in our program when we applied the log transformation on the entire vector.

Refer to the GitHub repository for additional information

Sources

- Service Provision Assessment (SPA), 2017-2018 https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA29/SPA29.pdf (French version)

- Groupe de la Banque Mondiale (World Bank Group). “Mieux dépenser pour mieux soigner: Un regard sur le financement de la santé en Haiti.” http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/835491498247003048/pdf/116682-WP-v2-wb-Haiti-french-PUBLIC-fullreport.pdf

- “DHS Data Users: Insights on Health System Quality from the Service Provision Assessments.” https://blog.dhsprogram.com/health-system-quality/

- KIRK, E., & KIRK, J. (2010). Cuban Medical Cooperation in Haiti: One of the World’s Best-Kept Secrets. Cuban Studies, 41, 166-172. Retrieved December 5, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24487233

- ICF. “Service Provision Assessment (SPA) Survey.” The DHS Program website. Funded by USAID. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/OF25/OF25.pdf

- ICF. “Infection Control and Readiness in Health Facilities: Data from Service Provision Assessment (SPA) Surveys.” The DHS Program website. Funded by USAID. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/OF46/OF46.pdf

Acknowledgements

This work was a product of dedicated collaboration. We thank Dr. Emmanuel Belimaire, Professor of Biostatistic and Clinical Epidemiology at the State University of Haiti for helping us structure the analysis and for providing feedback at various stages. We thank Dr. Theodule Jean-Baptiste, Public Health Researcher and Professor of Pharmacoepidemiology at the State University of Haiti for final review. We also thank Patrice Roc, UI/UX and Marketing Lead at Ayiti Analytics for finalizing the presentation and design of the final research paper.